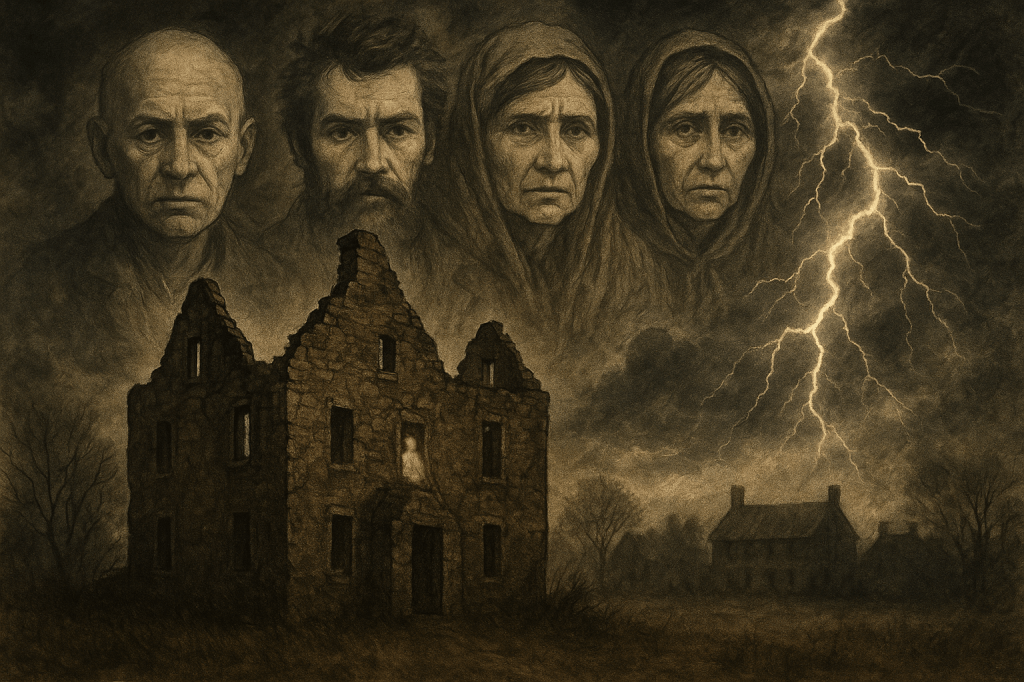

The Irish Ancestor That Wasn’t

I started with the belief that I had Irish blood, real Irish blood. The kind you raise a pint to. That idea was grounded in family lore from both sides of my family. We believed my father’s side, the Mastersons, were Irish and Italian. But DNA tests disproved that story. There was zero Irish ancestry from the Masterson line, and no Italian either. Instead, the results pointed strongly to England and Scotland. I was confused, so I began digging deeper. Unfortunately, it took years to sort it all out.

One name stood out: Sir Thomas Masterson, born around 1650 in Castletown, County Kilkenny, Ireland. The location seemed to fit. The surname felt right and was supported by genealogical records. I imagined someone caught in the struggles of a colonized people, perhaps even resisting British rule. I thought I’d found my Irish roots.

But the more I researched, the more the narrative shifted. Sir Thomas wasn’t Irish in the way I’d hoped. He was Anglo-Irish: English by origin, Protestant, and part of the ruling class that occupied Ireland. He wasn’t a victim of colonization, he benefited from it.

Then I uncovered something else: his descendants left Ireland around 1705 and settled in Virginia, where they acquired land and eventually enslaved people. His son left Ireland at age 30. Records show that Thomas Edward Masterson Sr. (1675–1754) emigrated to Virginia around 1705, between the births of his sons John and my seventh great-grandfather Edward.

This isn’t the kind of ancestry that makes you misty-eyed over Celtic music. It’s the kind that makes you pause, push the romanticism aside, and start asking harder questions. What does it mean to descend from people who weren’t the downtrodden, but the ones doing the treading? My informal family narrative had been off base. Learning the truth became a slow-burning obsession.

The Anglo-Irish: Rulers, Not Natives

To understand who Sir Thomas Masterson really was, you have to understand what “Anglo-Irish” meant. It wasn’t just about geography. These were English families, Protestant and privileged, granted land in Ireland by the Crown. Some arrived with Cromwell, others earlier during the Elizabethan plantations. They weren’t Irish culturally, religiously, or politically. They were settlers, and in most cases, they were the ones in charge.

The Anglo-Irish formed part of what became known as the Protestant Ascendancy, a small, powerful elite governing Ireland on behalf of the British monarchy. They held the land, titles, and political control. They lived in fortified manors, surrounded by Catholic peasants who spoke another language and followed another faith. Their role wasn’t to integrate, but to maintain order.

People like Sir Thomas were middle managers of empire. Men entrusted with land and authority to keep Ireland profitable and quiet, for the Crown. When rebellions occurred, they defended castles, not stormed them. When laws were made, they ensured Catholics couldn’t vote, hold office, or even own a valuable horse.

In short, the Anglo-Irish weren’t the oppressed. They were the face of the oppressor, cloaked in powdered wigs and Protestant virtue, dispensing control from behind stone walls.

It’s tempting to reach for the Irish identity as something scrappy and noble. But the Mastersons weren’t Irish in that way. They weren’t victims of empire. They were empire. And when their hold on Ireland loosened, many didn’t stick around to see what came next. They left, searching for another frontier, and another system to control.

Why They Left: Decline in Ireland, Opportunity in America

By the early 1700s, the Anglo-Irish grip on Ireland was slipping. The upheaval of the 17th century, Cromwell’s conquest, the Williamite wars, shifting royal successions, left estates in disrepair, loyalties in question, and fortunes diminished. The Protestant Ascendancy still held power, but the cracks were showing. Land became harder to maintain, especially for younger sons without titles or estates. The empire giveth, and sometimes, the empire casts you off.

Enter the American colonies.

To men like Thomas Masterson’s descendants, Virginia felt familiar. Land was cheap. Labor could be controlled. Power was up for grabs, especially if you were willing to get your hands dirty, or bloody. For many of them, the transition from Anglo-Irish gentry to American slaveholder wasn’t a moral leap. It was just business. Another system to exploit. Another population to dominate.

They brought their values with them: hierarchy, property, entitlement, and control. The names changed, but the model stayed the same. Instead of Catholic tenants, they enslaved Africans. Instead of English titles, they secured land patents. Instead of stone manors, they built plantations, or, in my family’s case, mills.

This wasn’t immigration as we like to frame it today. This wasn’t the starving Irish fleeing famine. This was the privileged class pivoting when their influence at home faded. And they didn’t come to blend in. They came to rule, again.

The Legacy We Don’t Brag About

We like to see our ancestors as heroes, immigrants escaping tyranny, rebels fighting oppression, survivors chasing a better life. That’s the story I grew up with and can honestly claim on my maternal Irish side. But we’re less comfortable with ancestors who arrived with power already in hand and used it to climb even higher, often at someone else’s expense.

That’s what I found in Sir Thomas Masterson and his descendants. Not rebels. Not refugees. But agents of empire, crossing oceans to preserve a system that had long rewarded them.

It’s not the kind of origin story that fits neatly into a family tree or a heritage festival. But it’s the truth. And it matters.

Knowing this doesn’t make me responsible for the past. But it does mean I don’t get to ignore it. I can’t romanticize the “Irishness” in my blood without acknowledging the domination that came with it. If we’re going to tell the story of where we come from, we owe it to ourselves, and others, to tell the whole story. Especially the parts that reveal how power was preserved, how wealth was accumulated, and how some families, mine included, benefited. Which is ironic, considering that by the time the Masterson line reached me, we were Catholic and working-class poor.

So I offer this not as a confession, but as an invitation: dig deeper. Question the tidy myths. And don’t be surprised if the roots of your family tree are tangled up in history’s darker soil.

Leave a comment